Originally published by Dallas Observer July 6, 2000

©2000 New Times, Inc. All rights

reserved.

( http://www.dallasobserver.com/issues/2000-07-06/feature.html/page1.html

)

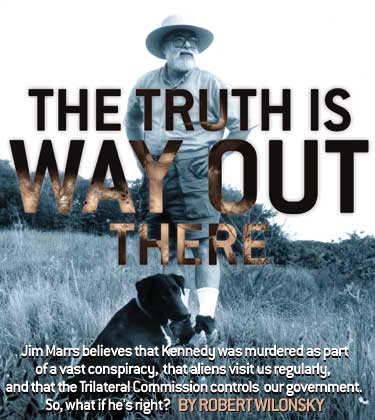

The truth is way out there

Jim Marrs believes that Kennedy was murdered as part of a vast conspiracy, that aliens visit us regularly, and that the Trilateral Commission controls our government. So, what if he's right?

By Robert Wilonsky

The Nut lives just outside a

small town called Paradise, a few miles northwest of Fort Worth. With his wife

of more than 30 years, The Nut inhabits 25 acres of land deserving of its

proximity to a town called Paradise, because even the still, damp air of summer

feels light and sweet here. The sunsets are a brighter shade of pink in the Wise

County town of Springtown; the grass grows a little greener. The Nut's home

resembles a log-cabin bohemian retreat, with a gurgling fountain, sky-high

sunflowers, a greenhouse and garage out back in which The Nut houses a cannon

and a 1930s Mercedes-Benz, and a pointed roof making it look like something out

of Hansel and Gretel.

Walk out the front door, and you

will find yourself on a mile-long path that snakes through lush, untouched

woodlands. Grasshoppers leap and bound by the thousands; the knee-high grass,

still damp from late-spring and early-summer rains, is alive. About halfway on

this walk, you stumble out of the forest and find yourself perched atop what can

only be deemed a cliff, which overlooks solid fields of neon green, each divided

by straight rows of trees that look like fences. Somewhere down there among the

brambles and bushes, says The Nut, is a creek that divides this land, which

exists to disprove the notion that North Texas' countryside is nothing but arid

flatland and barbed-wire fences.

The Nutwith his short pants and

denim shirt and hiking boots and straw hat and walking caneand his four dogs

walk up here when it's time to think, to clear the brain and focus on shadow

governments and assassinated presidents and spacemen who live among us.

"This," says The Nut,

pointing toward the spectacular horizon, "is where I come to be

alone."

It is hard to reconcile such a

placid, idyllic setting with the man who has lived on it since 1979. For a

decade, The Nutwho has a name, Jim Marrs, a most appropriate moniker for a man

who not long ago wrote a book titled Alien Agenda: Investigating the

Extraterrestrial Presence Among Ushas been among the most high-profile of

conspiracy theorists, though he would prefer you refer to him as a "truth

seeker."

Ever since the publication of his

first book1989's best-selling Crossfire: The Plot That Killed Kennedy,

a compendium of theories about who really murdered John Fitzgerald

Kennedy in DallasMarrs has been the poster boy for those who believe, and

those who do not. His reputation was cemented in (Oliver) Stone in 1990: When

the director bought Crossfire and hired Marrs as an advisor on JFK,

the author became the go-to guy for True Believers in search of a totem.

Yes, Marrs is given to rambling

monologues about all manner of subjectsfrom the government's cover-up of the

Branch Davidian torching in Waco to the crash of TWA Flight 800 to doubts about

William Shakespeare's authoring of his plays. But he remains a good ol' boy from

Fort Worth who speaks with the soft, warm twang of a man born and bred and bound

to the land on which he was raised. Marrs charms with a friendly grin. Talk to

him long enough, a few hours, and he will make you doubt your own existence.

"Jim is a very affable,

likable guy," says one old friend of his. "He reminds me of Santa

Claus."

Marrs, a former journalist for

the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, has been vilified in the mainstream media

and glorified on the Internet. Depending upon whom you believe, he's either a

man who views the world through "the warped prism of conspiracy

theory" (Publishers Weekly, in March of this year) or who writes

"must-read[s] for the entire population of America." The latter comes

from a fan on amazon.com reviewing Marrs'

latest book, the just-published Rule by Secrecy: The Hidden History That

Connects the Trilateral Commission, The Freemasons, and the Great Pyramids.

Either way, Jim Marrs can't be

ignored. Few in this country shout about The Truth louder than he.

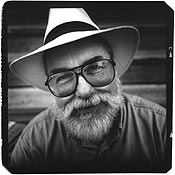

Mark Graham

Marrs' three books have all been published by well-respected New York houses,

not the crackpot press.

"Years

ago, when I was trying to tell people there was a big conspiracy to kill

Kennedy, I was the nut, the fringe guy, the conspiracy theorist, the buff, but

I'm used to it," Marrs says, sitting at a table in his dining room. He is

surrounded by trinkets from trips to Tibet, a page from the Gutenberg Bible

printed on the Gutenberg press, family portraits of wife Carol and the couple's

two grown daughters, Civil War memorabilia, a piano that goes untouched most of

the time, and an old coal stove that heats the home in the winter. No Kennedy

autopsy photos or drawings of giant-headed aliens adorn the walls.

"Now, almost everybody

that's awake and has paid attention knows there's something going on with the

Kennedy assassination," he continues. "There's still a lot of argument

about who, what, when, where, and how, but everybody understands that something

went on other than some lone nut got off a lucky shot. So that's all pretty

accepted, so now, of course, I'm on to other things, and now I'm still the nut,

the conspiracy theorist, so I guess I'll just be branded with that for

life." He chuckles, as though to prove how all right with it he really is.

It would take forever to prove or

disprove each of Marrs' beliefs; there are plenty of Web sites that support and

debunk his writings. Suffice it to say, Marrs is confident of only one thing:

Everything you think you know is wrong, and everything he knows he knows

is right. There is no arguing with the man. He has an answer for everything,

because, as he insists, "there is an answer for everything."

Yeshis answer.

"That's because Jim has a

tendency to want to believe everything," says Fort Worth-based

Kennedy researcher Dave Perry, an old friend of Marrs' who became critical of

him once he moved from writing about the Kennedy assassination to dealing with

alien visitation. "I once told him, 'Jim, you're more a

sit-around-the-campfire kinda guy.' If I wrote a book, nobody would buy it,

because it would be too cut-and-dried. Jim's books are entertaining, but not

necessarily accurate."

Still, Perry concedes, it's fun

to stop, if only for a moment, and consider what is unfathomable to the skeptic

and the cynic. What if Jim Marrs is right? After all, Perry says, for every

million words Marrs writes--and he is a prolific author, penning not only his

books but also essays for his Web site, www.alienzoo.com"maybe 10 are

true." [Marrs's web site is http://www.jimmarrs.com

. He writes a column for www.alienzoo.com

but does not own ita separate venture called

Alien Zoo doesKAR]

So, what if the government really

is covering up the assassination of John Kennedy? What if aliens have been

visiting this planet for decades, perhaps even living among us? What if a secret

cabal of politicians and bankers and media moguls has been dictating American

policy for decades? What if the Civil War was wrought by European nations

looking to divide and conquer the United States from within? What if the

government murdered the Branch Davidians in Waco and then destroyed the evidence

of their actions? What if an American missile downed TWA 800? What if the moon

is, in fact, a spaceship placed in orbit around the earth by ancient astronauts?

And what if John Kennedy was killed because he was going to tell the American

public about the existence of UFOs?

Seriously.

Or what if just some of what

Marrs believes is accurate and not the paranoid speculations of a man dismissed

by the mainstream media as a lunatic convinced the government exists to keep its

citizens in a placid daydream? What if only one thing is true?

"This sounds kinda

idealistic, but in journalism school...they taught you about trying to find the

truth and telling the truth to the public and letting them decide,"

Marrs says. "Look on both sides of the issue, look beyond the government's

pronouncementsall this stuff. And, hey, I bought into it. I really

bought into that. I thought that was what I was supposed to be doing."

Mark Graham

Since the 1989 publication of Crossfire: The Plot That Killed Kennedy,

Jim Marrs has been the poster boy for True Believers.

James Farrell Marrs, Jim's

father, came to Fort Worth in the early 1930s, seeking to escape the confines of

the coal mines. James left behind Logan County, Kentucky, and looked back long

enough only to bring his parents and his nine brothers and sisters to Texas. He

made enough selling steel to buy a house and rescue his family from the only

life they knew, since all the Marrs men were coal miners for as long as anyone

could remember.

Jim's mother, Pauline Draper, had

always lived in Fort Worth. Her daddy, who worked on the Texas-Pacific Railroad,

died when she was only 12, leaving her and her mother to fend for themselves.

Pauline's mother bought a house in the center of town, on College Avenue, and

opened a boarding house. James Marrs and Pauline Draper met on a blind date, as

best Jim can recall. Years later, Jim would meet his wife, Carol, the same way.

His parents were devout Baptists;

they did not drink or smoke and even frowned on dancing. But, their son says,

they were never judgmental or strict. In 1979, Pauline Draper Marrs even wrote a

romance novel titled Second Season, published by Fawcett (and, in France,

by Harlequin). The torrid little book features a hero named Jim and a heroine

named Carol. But Jim insists his mother's brief foray into the writing business

didn't move him to pursue his given profession. He picked up pen and paper on

his own, until a childhood passion became an adult's obsession.

"On a very deep level, my

parents instilled in me these ideas of honor, righteousness, courtesy,

allegiance to God and countryall that stuff you have to have as an

underpinning to put up with the slings and arrows of truth-seeking," he

says. "But they never led me into writing. They left me with a definite

impression I could make anything of myself I wanted to. My father never said,

'Son, you need to grow up and sell structural steel.'"

Jim was born on December 5, 1943,

on the south side of Fort Worth, a city boy searching for life on the prairie.

He hung out with his buddies in the meadows near what would become Benbrook

Lake, making lunch from bacon they would fry in a pan, and he spent time on his

kinfolks' farm in East Texas. It was inevitable that, years later, he would

leave Fort Worth for the countryside.

Marrs likes to say he began his

journalism career in high school when he joined the newspaper staff at Paschal

High School, where he drew the occasional cartoon and wrote editorials and

feature stories. But when he enrolled at North Texas State University in the

early 1960s, he enrolled in journalism courses because he discovered the major

required no math. It was a most pragmatic decision.

"But even then I was the

black sheep, because I started my own off-campus humor magazine, and I almost

got kicked out of school for sniping at the administration and calling them down

for all the bureaucratic stuff they were doing," Marrs says. "But I

hung in there, and I took my journalism courses, but it was the last semester of

my senior year before they finally realized, 'Well, damn, that Marrs character,

he's actually gonna graduate, and he's been the editorial page editor for the

campus paper and everything,' so I was finally invited to join Sigma Delta Chi,

which is now the journalism society.

"But for a while, I think

they tried to ignore me, so, you see, it's been like that my whole life. I've

always gone for the unconventional and the different. But that's OK, because if

you study somethingany subject, I don't care whatever it

isand come

to know the truth of what's going on in that subject, you've got the truth as a

defense against everybody."

Marrs was asleep in his dorm room

when events transpired at 12:30 p.m. November 22, 1963, to wake him from his

reverie. Like Jim Garrison in JFK, Marrs would sleep no more when he

heard John Kennedy had been shot while driving through Dealey Plaza in Dallas,

gunned down by the bullets of an assassin. His initial reaction to the news of

the president's shooting was one of relief, happiness. His roommate woke him to

tell him what had happened, and all Marrs could say was one word:

"Good."

By his own admission, he was then

a "typical Texas redneck" who thought Kennedy was a handsome man

determined to hand the country over to the liberals and blacks. He had no use

for the man or his utopian vision of one nation under Camelot. But like the rest

of the country, he was stuck to the television, watching every second of news

coverage. When Walter Cronkite showed up at 1 p.m. to announce Kennedy's death,

Marrs was watching and, he insists, thinking about how he could get involved in

covering the biggest news story to come out of North Texas in decades. Even now,

he has all the newspaper clippings from November 1963. They would, in time,

become his life's roadmap.

First, though, there was school

to finish, which he did in 1966. But he put his life on hold, convinced he was

going to get drafted by the Army and sent to Vietnam. It was inevitable. He took

a job with a men's clothing store in Fort Worth and waited, taking draft

physical after draft physical but never getting his notice. He was ready to go,

a patriot prepared to die keeping the Commies at bay. Yet the more he read about

the burgeoning war in Southeast Asia, the more convinced he became that the U.S.

wasn't in Vietnam to win.

He thought about high-tailing it

to Canada, which seemed like the coward's way out, or he could sit around and

wait to get drafted to go fight a no-win war. Or he could go back to school,

which he did in 1967, enrolling at Texas Tech University in Lubbock to get his

master's degree. A year later, he left school and came home, this time for a

full-time job at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, where he was put on the

police beat, a romantic assignment for a 25-year-old kid obsessed with chasing

ambulances and plane crashes and traffic wrecks. He liked the sound of sirens,

the scent of blood.

When the Army finally came

calling in 1968, Marrs ended up working military intelligence in a reserve unit,

which was hardly as dramatic as it sounds. He spent his time translating copies

of French and German magazines that could be bought at any high-class newsstand

in downtown Fort Worth. By the time he was due to go on active duty, it was

discovered he had a bum shoulder, which the Army offered to repaireither that,

or Marrs could get his release. He chose the latter and returned to the Star-Telegram.

Every now and then, Jim would

find himself in Dallas covering a story, and sooner or later, his conversations

with local cops would always turn to the Kennedy assassination. He was becoming

convinced Lee Harvey Oswald did not act alone, despite the findings of the

Warren Commission, and thought it might be fun to snoop around a little. So he'd

take care of his story, then interview police officials about what really

happened in November 1963. Over time, the trail would eventually lead him to the

doorsteps of Oswald's mother, Marguerite, and George and Jeanne De Mohrenschildt, friends of Lee's. They convinced Marrs of what he already knew to

be true: Lee Harvey Oswald was set up by the government.

He'd spend the rest of his life

trying to prove it.

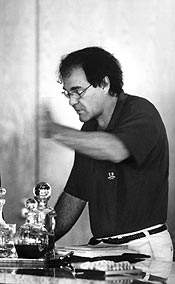

Robert Zuckerman

Oliver Stone based his 1991 film, JFK, partly on information found in Crossfire.

The phrase "conspiracy

theorist" is an insult to those who believe. To them, there are no

theories, only ignored truths. The government, they will tell you, has lied to

us for decades; what we know are only the fabrications spoon-fed to us by

official documents and press releases and smiling politicians. We are blind,

stumbling around in a smokescreen. The so-called theorist? His eyes are wide

open, and it is his job to lead us through the darkness. Those who are called

"conspiracy theorists" are ridiculed by the mainstream until they

become punch lines and punching bags.

No one knows this better than

writer-director Oliver Stone, who was once hailed as the great leftist filmmaker

of the 1980s until the release of JFK in 1991. Using Marrs' Crossfire:

The Plot That Killed Kennedy and much-maligned New Orleans District Attorney

Jim Garrison's book On the Trail of the Assassins as his guide, Stone

threw every possible theory against the silver screen, hoping some of it would

stick. Garrison, portrayed in the film by Kevin Costner, had long been

castigated for trying to prosecute a New Orleans businessman for conspiring to

kill Kennedy, but Stone insisted on using him as his righteous hero. As a

result, Stone was subjected to the same ridicule as Garrison: He was called a

liar at best, a deranged fool at worst.

Stone insists that his career was

ruined by the reaction to JFK, that his subsequent films (among them Heaven

and Earth, Natural Born Killers, and Nixon) were dismissed by

those predisposed to writing off Stone as a conspiracy-obsessed lunatic lost in

a hall of mirrors. Commentator George Will branded Stone "an intellectual

sociopath, indifferent to truth"; Newsweek ran a cover story titled

"The Twisted Truth of 'JFK': Why Oliver Stone's New Movie Can't Be

Trusted." And that was just for starters.

"It outrages me some of the

cheap shots taken over the years, and the same thing happened to Garrison,"

Stone says, taking a break from writing a new film about AIDS and Africa.

"When he went on Johnny Carson, he got exactly the same s--- I did when I

went on Letterman and Nightline. They were the exact same

questions: 'Are you paranoid?' 'Are you a conspiracy theorist?' Who gives a

f---? Life is half conspiracy, half accident. Who gives a s---? For them to

deny conspiracy is the stupidest single argument when we've had so many

conspiracies, including the biggest one, the Communist conspiracy, where you

raise an entire generation to live in fear of a monolith Communist front moving

across the United States. It was insane, and then they don't even talk

about that. They always dismiss anyone who's trying to do something as a nut, as

a conspiracy theorist, which is a very demeaning word."

Marrs was not the first man to

write of a sinister plot to kill the president. Nearly half a dozen books were

published in the years immediately following the assassination, including Mark

Lane's seminal Rush to Judgment. But Stone optioned Crossfire

because it was the bible of conspiracy theories; it contained every single

explanation offered by those who couldn't accept the Warren Commission's

findings. It was complete: There were government agents and Texas millionaires,

Dallas cops and Mob hit men, Cubans and CIA operatives, J. Edgar Hoover and

Lyndon B. Johnson. Not a single dart was spared. Marrs heaved them all.

The assassination had become his

obsession. He wrote the occasional story about Kennedy's death for the Star-Telegram,

and by 1976 he had been asked to teach a course about it for the University of

Texas at Arlington, a course he still teaches. Lord knows he had time to spend

on it: He quit the paper in 1980, worked some freelance ad jobs in Dallas, and

even started a couple of freebie newspapers, but nothing held his attention like

John Kennedy. By the time Crossfire was published by the New York-based

house Carroll & Graf in 1989, he had spent more than a decade researching

it.

By the late 1980s, myriad studies

revealed that a good portion of the American public believed Oswald did not act

alone, if he indeed was a gunman at all. The government had admitted as much in

1979, when the House Select Committee on Assassinations concluded there had been

at least one other shooter who escaped the crime scene.

"But the powers that be tend

to blow that off and don't emphasize that, so everybody thinks there's still a

big controversy about the assassination," Marrs says. "Even in 1980 or

'81, the majority of people who came to take my course started off with the idea

that Oswald did it all by himself, but that began to shift by about 1984. From

that point on, not one person ever showed up for that course who would admit to

thinking that Oswald ever did it all by himself. There was a real turnaround in

public perception, and when the Stone movie hit in 1991, that really got things

going. Crossfire and Stone's movie were really popular and hit the big

time not because we were changing people's minds, but because we were

demonstrating something they had already come to know. In other words, the

timing was really good."

But Marrs prefaced Crossfire

with a warningor, as Dave Perry says, an easy out. "Do not trust this

book," reads the opening line of the book, giving Marrs leeway to write

whatever he wanted, to include every theory no matter how plausible or asinine.

(Alien Agenda and Rule by Secrecy contain similar disclaimers.)

Even Stone ignored certain portions of Crossfire.

"I'm not always in agreement

with Jim," the filmmaker says. "There were some things I didn't follow

up on, like the Mob thing, because I really had my doubts about those people.

But he was very helpful."

The book and film turned Marrs

into a celebrity on the conspiracy circuit. The sane and crazy sought him out,

journalists begged him for quotes, and enrollment in his course at UTA rose

considerably. Even now, his phone never stops ringing: The curious seek his

wisdom, while those who claim to have information about the death of Kennedy

seek his attention. Somelike James Files, a convicted cop killer in Illinois

who now claims to have been the Grassy Knoll gunman--are taken seriously,

despite the fact that few researchers believe his tall tale. Others are given

their due consideration. After all, Marrs argues, you never know from under

which rock the truth will crawl.

"They call a lot,"

says his wife, Carol. Her tone of voice suggests she would rather they not.

"But I always give them a

fair hearing, OK?" says her husband. "And they sometimes have some

valid points, and sometimes they have some valid information. A lot of the

times, it's a guy who says, 'I'm a 16-year-old high school student from Kansas.

Do you think Oswald did it all by himself?' But I give them as much as I

can."

Had Marrs stuck to researching

the Kennedy assassination, to uncovering that single and monumental

"truth," his tale would be no different from those of the hundreds of

authors who have published books on the subjectthose who think Oswald acted

alone, and those who think he never existed at all. He would have disappeared on

the crowded bookshelves, gotten lost in the dusty remainder bins.

But somewhere along the way,

Marrs stopped peering inside empty coffins and turned his eyes skyward. And when

that happened, the conspiracy theorist became The Nut.

Mark Graham

Jim and Carol Marrs lead separate lives: She teaches high school, while he

solves the world's problems.

There came a time in the mid-'90s

when Jim Marrs grew tired of talking only about John Kennedy. Even obsessions

become wearying when tended to forever. He then began asking friends,

publishers, students, even his good-ol'-boy neighbors in Springtown what next

great question they wanted answered. He insists they all offered the same reply:

UFOs. Do they really exist? Are little green men out there? Are little green men

right here? And if so, has the government covered up their existence?

In 1997, Marrs gave them their

answer, a book titled Alien Agendapublished by Harper Collins, not some

crackpot housewhich claims the government has known about aliens since at

least the infamous 1947 "spacecraft" crash in Roswell, New Mexico, but

has orchestrated a campaign of "denial and ridicule": Insist aliens

don't exist, and make fools of those who believe they do. The book's an

enjoyable read but hard to take at face value: Marrs spends a great deal of time

writing about remote viewing, the use of psychic ability to travel through time

and space to spy on one's enemies. He insists he has done this, just as he

insists government officials and military officers have told him of the Army's

experiments with remote viewing.

On this point, as with everything

else, he is adamant; he knows it is possible. But even the most willing

or the most susceptible would likely find this hard to swallow whole. It is too

much the stuff of science fiction, as is a story Marrs offers up in Alien

Agenda suggesting Kennedy was really killed because he was about to reveal

the existence of UFOs to the American public. If you believe the tale, he even

told Marilyn Monroe, who was going to hold a press conference revealing John and

Robert Kennedy's deep, dark secretsone of which was a memo confirming

extraterrestrial visitation. When pressed, even Marrs says he doesn't "buy

into that."

Which, says Dave Perry, is

precisely the problem with Marrs' books.

"I have an autographed copy

of Crossfire that says, 'Always question authority,'" says Perry.

"Where Jim hurts himself is, he won't take a stand on anything. As the

years have passed by, he has moved more and more out of real mainstream research

methods into ones that are more, well, esoteric. They don't require the

level of expertise he used to use in the past. Crossfire was like the

encyclopedia of the good, the bad, and the indifferent. Now, he mixes some

common-sense information that's already known with some strange and bizarre

activities. Over the years, I've come to the conclusion of what has changed is

his attitude: He's getting more into the fairy-tale area than he used to.

"I mean, it wasn't until the

last five years he got enamored of remote viewing, which has a questionable

legacy. I used to go to his Kennedy class at UTA and razz him, poking holes in

his theories. Once I said, 'Why don't you get one of your remote viewing friends

to solve this stuff?' But you can't get him hostile. He's so low-key. The fact

is, Jim wants to believe in Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny. All of his

responses are from the fringe element. The legitimate people dismiss him, which

is sad, because there's some great stuff in Crossfire and even Alien

Agenda. There are good things, but it's lost in all the hype."

In Alien Agenda, Marrs

speculates that aliens do indeed walk among usthat they are indeed "here

to help us," as one of his sources says. Another offers

"evidence" that aliens have given us, among other things, our

religions. But when asked whether he believes such things, Marrs laughs and says

only, "I'm an agnostic."

That's too easy an answer, he is

told.

"Well, it may sound easy,

and it may sound glib, but it's the truth," he says. "I've never seen

a UFO, but there are enough credible people I've talked to who said this is a

legitimate deal. Even the most skeptical scientists have all pretty much

believed that, in all likelihood, there is intelligent life somewhere out there.

I hope there is. I hope we're not the epitome of intelligent life. That's the

question I keep asking myself: Is there intelligent life on the planet earth?

And I only find occasional glimpses of it."

Marrs, his wife, and his dog walk off into the sunset.

This is how secretive the

Trilateral Commission is: Its North American Group phone number is (212)

661-1180, listed next to its New York City address under the "Contact

Us" section of its Web site, www.trilateral.org.

The numbers and addresses for the European Group and Japanese Group are

similarly listed, as is a roster of the organization's 37-member executive

committee, a list of its publications, a brief history of the organization, and

transcripts of speeches delivered at the commission's April 810, 2000, annual

meeting in Tokyo. And that's just skimming the surface.

The Trilateral Commissiona

27-year-old organization made up of 335 members from North America, Japan, and

Europe, founded to "foster closer cooperation" between the regionshides in plain sight.

This is how hard it is to speak

to a member of the Trilateral Commission:

"Hello, I'm a reporter for

the Dallas Observer, and I would like to speak to someone about a new

book by Jim Marrs titled Rule of Secrecy, which deals with how the

Trilateral Commission is a secret society trying to take over the world's

governments."

"One second, please,"

responds the amused woman on the other end of the line. Fifteen seconds pass. A

male voice picks up the line.

"This is Charles Heck."

Charles Heck is the Trilateral

Commission's North American Director, meaning he's just below North American

Chairman Paul Volker (former chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve System) and

North American Deputy Chairman Allan Gotlieb (ex-Canadian ambassador to the

U.S.) on the totem pole. Heck's been with the commission almost since its

inception in 1973"since I was a young squirt," he says,

chucklingand has heard all about how the Trilateral Commission is a sinister

entity out to control U.S. and foreign governments. He spends a great deal of

time going on radio talk shows trying to dispel the "remarkable

mythology" of global domination that surrounds the organization. Heck

doesn't recognize the name Jim Marrs ("Jim Morris?"), but he's

quite familiar with his tale.

"It seems to have gotten

going in the late 1970s, when Jimmy Carter was elected president," Heck

begins, no doubt for the umpteenth time. "Carter had been a member when he

was elected president, and when he went to the White House, he appointed a

number of U.S. Trilateral members to various positions in his administration.

David Rockefeller was the main figure in the creation of this organization, and

anyone named Rockefeller inspired this sort of mythology, and somehow the notion

was that David Rockefeller and everybody else had gotten together to elect Jimmy

Carter and bring all these other Trilateral Commission folks into

government--even though David Rockefeller was supporting Gerald Ford in 1976. If

you already had a somewhat conspiratorial bent in terms of how your government

was run, you thought you found the smoking gun just by noticing a bunch of these

folks were members of the Trilateral Commission. That was all the evidence you

needed without knowing anything else about it at all."

Conspiracy theorists have long

believed the commissionnot to mention its precursor, the Council on Foreign

Relations, and other so-called secret societieswas out to create a one-world

government run by the most powerful of the world's elite: bankers, businessmen,

media moguls, politicians, and so forth. They bandy about phrases such as

"one-world government" and "globalization," terrifying

themselves with the notion that our elected officials serve only themselves, not

the public.

Marrs will say he doesn't

necessarily know whether globalization is good or bad, only that he fears an

Adolph Hitler will one day seize control of the one-world government. Sitting in

his living room, speaking through his white beard and warm smile, he prophesies

doom.

Meanwhile, Carol Marrs prepares

lunch in the nearby kitchen: Reuben sandwiches, bratwurst, and cold German beer.

It is a beautiful day in Springtown. Someone should send the Trilateral

Commission a thank-you note.

During lunch, it becomes apparent

that Jim Marrs lives with his greatest critic, his wife. She has little interest

in the Kennedy assassination, found Rule by Secrecy "difficult"

to read, and is vaguely intrigued by the UFO stuff. She's a pragmatic high

school art and drama teacher in a small, football-obsessed town. Jim can go on

trying to topple one-world governments, but there are still bills to pay and

meals to prepare and students to coach for drama competitions and, in the back

yard, a pot-bellied pig to tend to.

"Jim and I kind of live two

separate lives," Carol says, shooting a smile her husband's way. "I

mean, I do my thing and he does his thing, and I know a little bit about some of

it because I read his books, but I don't have any memory capacity. God, I mean

it just amazes me how he rattles off all these facts and everything. I can read

it and still go, 'What?'"

"This is why Carol and I

make a good couple, really," Jim says, returning the grin. "She's very

earth-mother, very practical. She has her feet on the ground, and I have both

feet firmly planted in mid-air. I'm out there just thinking about..."

His wife interrupts, and what she

says next explains all you will ever need to know about Jim Marrs. It turns out

he is not a nut at all. Rather, he's just a guy living in the countryside who is

convinced he will, one day, make a difference.

"I'll say, 'Jim, why don't

you help me? And he will say, 'Not right now. I'm taking care of the world's

problems.'"

They share a small laugh, and he

gives her a look that says: Yes, yes I am.